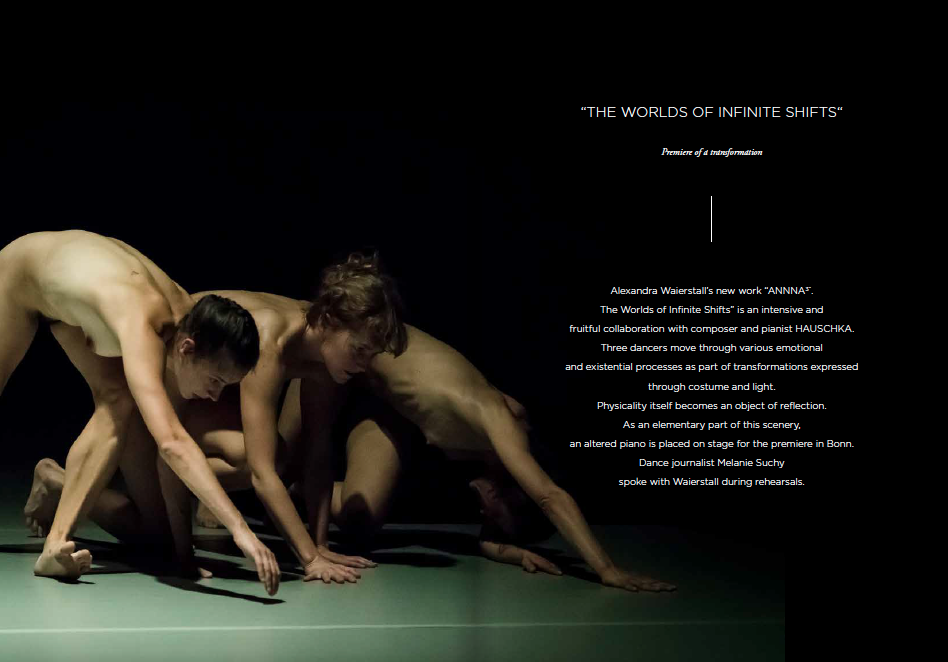

Melanie Suchy (MS): Costume is important in this piece, which is quite unusual in contemporary dance. The dancer’s body is sometimes hidden entirely, sometimes partially concealed and sometimes completely bare.

Alexandra Waierstall (AW): These are transformations. With the last garment, the slowly moving body transforms into matter before disappearing, becoming light and only reflecting.

MS: Speaking of concealing and unveiling: Is it about visibility − or invisibility − of the body?

AW: At the very start of rehearsals I said: The body emerges in darkness and disappears in the light. That became the basis of the piece. I like to use a little motto as something to hold onto if we lose our way in the creative process.

MS: Do you develop such statements while writing?

AW: Yes, writing is part of my working process, regardless of the limited production time in the studio. I write every day, usually from 6 to 8 o’clock in the morning. It’s all about artistic expression, and not about grants or organization or the like. This requires discipline and dedication, but does not always have to be effective. I need it to keep the “machine” running. It means that working in the studio is not such a tough start.

MS: A continuity can be observed between your works. Not repetition or self-quotation, but the latest pieces always seem to have learned something from those before them.

AW: They are connected with each other, through certain movements or principles. The performers and their idiosyncrasies create diversity and complexity. By contributing a solid foundation of much preparation and continuity, fragile situations can occur and the dancers bring invisible parts of my thoughts to light.

MS: You started the practice of writing, as you said, out of necessity, out of having neither studio nor dancer for working continuously?

AW: Yes, it started in 2010, with the duet “Tomorrow in Present Tense”. A man sits on the stage and describes what is happening there. He observes Evangelia. But what he says never happens exactly at that moment − he is always slightly ahead or behind. Or even far ahead. Once he says: “she’s on a silver floor”. It was only two years later that I had a silver floor in one piece.

MS: Does anything from a different piece feature this time?

AW: Yes, something from “(T)here And After”. Anna takes off the costume; a naked body is revealed and is dressed again and becomes part of the group of five. Like a: “Who am I?” – “There, this is you! Find yourself and the others.” Also a part of one of Anna’s solos at that time, where she sees nothing. I tell her: “With that you suddenly find yourself in another piece!” She becomes that woman, becomes materiality and then light, this time accompanied by two women – hence the title with the three NNN – as if they had a common mind, as if they were being moved by the same thought. But its embodiment is different.

MS: The dance looks as if it was first invented on stage and yet is choreographed, i.e. set relatively precisely beforehand?

AW: Many choreographers aim for synchronized movements when the content focuses on a common idea. I don’t: Something is the same, yet always different in the bodies. There is a moment when they are all “together“, but I don’t take away the soul of the performers. I try to create space for them. To bring the event to life. What they do is specific, but I don’t polish them. Bodies that move in the same way often look like zombies or dolls. I look for the personality.

MS: In what way?

AW: I try to bring the dancers into states of survival within the movement material. Out of the safe position of “I know what the choreographer wants“. I always leave a little space, a little ambiguity, in which they themselves have to take responsibility with micro-decisions.

MS: Within the scope of tasks that you give?

AW: Yes, these small intermediate movements in the big picture in space and time which, in turn, is set in a very clear and stable manner with regard to choreography. They have to decide for themselves and every time anew in the moment of the event.

MS: Regarding the term heroic, which you mentioned in an earlier conversation in relation to the Beethovenfest motto “Destiny”: The “heroic“ emerges with the “effort of survival“. So you, at first quite practically, set the dancers survival tasks in the dance itself, for which the audience can also have its own associations?

AW: Challenges: the thick fabric of the costume in relation to the movements; the movement within the limits of repetition, speed and muscular tension. The limits of perception: To perceive the other without being able to see and hear them well. To have to read and feel the space through the skin. The feet often act as eyes and the arms become antennas.

MS: How does the choreography meet the music and vice versa?

AW: Volker looks at the dance material and adjusts the prepared music to the scenes. I don’t want it to be like film music, I want the music to act like a fourth body, like an organ. In the beginning as a heart that pumps rhythmically. Then the silence, which for me is like the intestine. The next part is more like the nervous system, a little higher, lighter; and towards the end the music becomes like blood, fluid, and no longer as complex. That’s how I imagine it. At the moment I don’t know how we will end it. Where are we going? Possibly into the void, out of the performative, out of the theatrical. No effort, no heroism, no more effort of survival, just: there.

MS: Do you want to say anything else about the start?

AW: Loud music – at a very unusual point in the piece. For how long can a sound get thicker, fuller and louder? You see one body, then the next, and the next. The illusion that this is a single body. Or many bodies. A long dance. Then the break. For how long can we be quiet? A challenge for a musician! Just sitting there, not being productive. Then the dancers move very dynamically, like animals, you don’t know whether they are goddesses or tigers or birds, people, whether they have just been born or are ancient.

MS: During rehearsals, I noticed the jumps with raised knees.

AW: It’s not about the jumps, it’s about the bodies being tired afterwards. If I now ask the dancers for quick movements, the sense of survival comes into play. You don’t think about aesthetics, about leading the movements, but are in direct, attentive contact with yourself and the others.

MS: So you take the security of the familiar away from the dancers?

AW: Yes, what I look for in all my works is to really see the dancers. For that I have to hide or shake them nowadays. Because at some point they gave me what they thought they knew I wanted and I no longer saw them. So I changed my way of working. To achieve the same goal.

In the rehearsal I don’t say: Not like that, not like that…! But: Change this – something very small. Relax the jaw. Or: Listen only with your left side. Something happens immediately in the entire body, it pushes it out of its usual balance. That’s how I edit them, compose them, sculpt them from the inside. And I really want them to look good during this process.

MS: What’s special about working with Hauschka?

AW: Four years ago I just missed his concert at the Hombroich rocket station. I had read that he works with the concept of “abandoned cities“, on which I was also planning a piece. The Tanzhaus NRW then put me in contact with him. Volker looked at my “Matter of Ages“ and was blown away. A fan. That’s why I’m so happy to work with him.

MS: You cooperated on three pieces in 2015 and 2016: “A city seeking its bodies“, “(T)here And After“ and “And here we meet“.

AW: The continuity is nice. What is special is his deep understanding of John Cage’s principles. Cage has inspired much of my choreography, such as working with silence. I grew up with his books and with what he did with Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg.

Volker composes how I choreograph: A living space always remains free for the coordination of the elements in the live action. He has the piano keys, the computer and what he throws into and mounts on the piano. He can’t control exactly how the balls fall. So there is always a element of the random in the micro-actions. Similarly, in a single movement, the rest of the body follows, responding a little differently each time. It is precisely in this in-between, in sound and movement, that magic happens. We are probably quite similar in this approach.

Comments are closed.