Alexandra Waierstall’s work “A line, a gaze, a horizon” premiered at the Cyprus Choreography Platform in November of 2020, a year that was riddled with the Covid-19 pandemic, illness, and uncertainty. Following a strict lockdown in the spring of 2020, the dance scene in Cyprus continued to present new works with festivals having to adjust to constantly changing measures imposed by the Cypriot government to attempt to slow and stop the spread of Covid-19. The Twentieth Cyprus Choreography Platform took place right before a looming lockdown, which shut down theatres once more. The days and weeks before the festival were filled with anxiety and uncertainty whether the new works would be shown before a live audience. When it finally happened, the atmosphere at the theatre was filled with hope, optimism, and gratitude that live dance was taking place in front of an audience and that this may be the last chance to see some dance before another lockdown took hold.

I have been following Waierstall’s trajectory as a choreographer from the beginning of her career and watched her aesthetic mould. Her works are characterised by minimal and stark visual representation where movement takes the lead role. Always working with stunning dancers, Waierstall seems to gently guide them into her approach to moving without forcefully dictating her style of moving and steps. The movement in her works has a particularly malleable quality – it feels like air trapped under a parachute. The dancers, under the choreographer’s guidance, employ their whole body whilst emphasising lines of the limbs. Yet, possibly the most exciting aspect of how dancers move in her choreographic works is the unexpected twists and spirals which redirect the initiations of the movements and its vectors into surprising shapes. The dancers flow through movement without jerky interruptions, yet the movement communicates a tension that implies the complexity of the body and its socio-political possibilities in an abstract way.

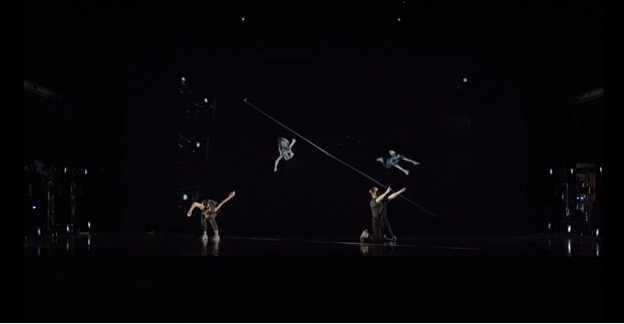

Inspired by the overwhelming shift to digitally screening dance in 2020, Waierstall’s work “A line, a gaze, a horizon” explores the effects of the camera and screened dance on choreography, whilst also commenting on events of 2020, the pandemic, and its effect on dance making and everyday life. This essay examines the structures of the work and its implications, by presenting a description of the work, images, and analysis of dynamics of the work as seen through my eyes. The piece is performed by three performers, Arianna Marcoulides, Rania Glymitsa, and Savvas Baltzis who is simultaneously the videographer. The work is accompanied with a recording of spoken word written and performed by Waierstall, some of which is included in this essay. This work begins with a projection of a white light across the entire cyclorama. It is bright and hard to discern.

Ten, Nine, Eight…seven, six…five, four

The first dancer (Arianna Marcoulides) enters the stage wearing a greyish blue tunic, leggings, trainers, and a protective black face mask over her nose and mouth. With a simple decision to include a face mask, Waierstall summarises and captures 2020 – the year plagued with the Covid-19 pandemic and mask wearing. She also makes a political statement that she believes in science, the need to protect others, and safety of her collaborators above all. Marcoulides remains static whilst the image on screen begins to move capturing a wall, then the fire extinguisher, eventually catching the stage side lights and Marcoulides from the back revealing the complex structure of the work involving the live video projection performed by Baltzis.

Hand, Elbow, Blue. Walking Backwards.

As Marcoulides lifts her arm, the spectators are faced with two images of the dancer — the live one allowing the audience to see her three dimensionally from the front and a screened one featuring the dancer through the glare of four side lights located on the opposite side of the stage to the videographer.

Oslo. Paris. Milan. Left arm rising three centimetres… ball of the foot. Nicosia. Tokyo

Marcoulides performs an expansive lift of the left arm whilst lifting her knee to take an exaggerated step backwards making a simple step into an artistic statement. The videographer, also wearing a mask, and long black billowy coat, appears stage right holding his camera. As he moves forward, the image of the dancer on screen enlarges exposing a simple filming technique of alternating the size of the body through the position of the camera and a new dance emerges of the shifting relationship between the three subjects — the dancer on stage, projected image of the same dancer on screen and the videographer. Waierstall allows the audience to choose who to concentrate on, which is characteristics of live performance and more specifically, post-modern dance which stages many actions simultaneously inviting an active and involved audience reaction.

I wish I was more still…

The relationship intensifies as Baltzis moves in closer allowing the screened image of the dancer to grow and overwhelm the scrim as she grows beyond her physical size due to the manipulation of the image through camera work. He circles her, crossing in front of her but captures her back again therefore allowing multiple perspectives of the same movement. Her movement is slow and sustained, expansive and showing beautiful lines of her arms. The dim lighting catches the exposed skin of Marcoulides’s arms, neck, and partially covered face. But the image captured by the camera and projected onto the screen shows more detail, more colour variation in the costume, and creases in the fabric, which offer texture to the kinaesthetic corporeality of the live presence on screen. As the videographer keeps moving, he captures a fragmented image, showing the dancer’s body from the shoulders to the floor directing the screendance there and then using traditional techniques of filming dance.

The camera changes its angle. Can see me now from behind

As he crouches in front of Marcoulides, the spectators see his back, a front view of her shifting through a lunge and the same much larger and fragmented version of her on screen. As the camera zooms out, the image is multiplied manifold in a double mirror effect. Suddenly, the performative space is filled with a chorus of dancers in perfect unison stemming from a single live performer and her partners, the camera, and its handler. As Marcoulides performs a slow, eloquent turn and lifts her arms shifting into a large plie in second position, the videographer shifts sideways slightly, moving the placement of the screened replicas of the dancer. Baltzis moves the camera downwards and alters the composition on screen eliminating many of the screened dancers. Marcoulides moves her head and upper body down, and at this moment only two images of her on screen accompany her, whilst also catching the exit stage door drawing attention the architecture of the theatre. He approaches the dancer offering a close up of her buoyant movement and captures Waierstall’s movement aesthetic of the body simultaneously stretching and moving in multiple directions whilst maintaining contrasting calm tension. Their duet continues as he circles her, capturing the side lights and industrial composition of the backstage.

Sometimes infrastructure, or structures we depend on shift…These can be natural things, like how much the sun shines and how much it rains

The videographer continues to spin and re-directs attention onto the auditorium capturing the Covid-19 mandated organised audience with spaces between the occupied seats and wearing masks.

Fingers … Hand … Invisible Threat

Marcoulides continues to move onstage but another performer emerges from the audience. Rania Glymitsa slowly rises out of her seat and pauses. The videographer moves in closer allowing her image to appear on screen amongst the audience members. Although, Marcoulides continues to dance on stage, the camera has re-organised the composition of the work, allowing a view to the audience that the audience would not be able to access without the camera lens and its commanding attention as it captures the auditorium and places all of the spectators on stage as a screened chorus behind Marcoulides and Baltzis.

Electricity… two meters…. three meters. Toronto. Malmo

Glymitsa makes it out of the seats and looks directly at the camera forcing the audience to face a large image of her masked face and expressive eyes. She climbs the stairs and the videographer appears on stage again walking backwards as Marcoulides halts her movement. The choreographer presents a new relationship: Marcoulides upstage, stage right facing diagonally forwards, Baltzis stepped in the same orientation downstage, stage left and the large image of Glymitsa screened between the two materials bodies on stage.

A line, horizon, a gaze into the infinite

Glymitsa steps on stage, looks at the videographer and proceeds to draw a line on the floor with white sticky tape. The videographer captures her moving backwards, showing an image on screen that shows both dancers — one standing still and one crouching down and moving backwards placing the tape on the floor. At the same time, the audience sees the front view introducing a complex visual design out of a simple arrangement that shows various dimensions, perspectives, and live and screened dancers amongst multiple lines created on stage and screen with the white tape.

Marcoulides walks across the stage and disappears from the screen, while Glymitsa continues to pull and place tape on the floor.

Ten, three, one and a half. I move slow and I hear my heart beating

Glymitsa’s corporeal image is augmented and replicated on screen, along with Marcoulides who has entered the field of the camera. But the screened images do not simply multiply the number of dancers, they also distort the stage and screen as the image of one dancers curves on top of the other creating an arc in the architecture of choreography of screened and live bodies.

Twelve. Twenty Seven. Sixty Five.

As Marcoulides begins to do gentle jumps, the multiple screened images of her are out of sync creating a syncopated rhythm that is a result of the technological pattern but quickly this concept disappears as the camera moves away from Marcoulides leaving only the live dancer to continue to jump.

Again. Two. Three. Five.

The videographer walks off stage and Glymitsa walks back on and they casually bypass each other so the videographer captures the side stage area, and then Glymitsa from the back carrying a microphone stand and Marcoulides who is still jumping.

Nine. How fast can you run?

Glymitsa joins her and they both jumps facing each other with the microphone stand between them and a large, screened image of the back of Marcoulides. They jump in perfect rhythmic unison creating a soundscore with their trainers hitting the marley floor and their laboured breathing, but the visual rhythm of their physical and aural movement is distorted as the videographer circles them and projects multiple images of both dancers whose jump appear in syncopation due to the distortion of the camera and the delayed projection.

Eight

They abruptly stop

Seven

Marcoulides exits stage left. Baltzis follows Glymitsa offstage leaving the stage with a large screened image of the back of her head and neck. She disappears too and the stage is empty but filled with a projection of a striped staircase.

There is a wild place, there is a wild place, not too far from here. This place wasn’t always so wild.

What proceeds is an homage to the theatre, its construction, and the possibilities of the camera to transcend physical limitations, open perspectives, and offer new views. The videographer exposes the metallic structure of the winding banister, the lines of ropes that lower and hold lighting rigs in place. Their texture is stunning. Baltzis captures the ropes, metal rigs, electrical plugs and cables exposing the architectural structure as mundane, matter of fact and magical. By reaching into this space of the theatre, hidden from the audience, and even performers, Waierstall changes the notions of site-specific choreography. The theatre becomes integral to the work as it is explored through various perspective through the camera. The two dancers re-enter the stage and Baltzis captures them from above using a classic dance on screen methods of the overhead shot, which presents an alternate and impossible live view to the theatre audience of the two dancers performing in a space divided by the white tape. The multidimensional experience of seeing movement invites a new kinaesthetic empathy — one of understanding the weight of movement of live dancers, and one of screened images which provides a glimpse into the design of movement. Accompanied by tense, industrial music, the work adopts a sustained tension.

My heart accelerates. I am four meters off the floor.

The dancers are transported onto a different site, as the videographer shifts to the bridge of the overhead space, making it seem like they simultaneously occupy the traditional stage and the upper level of the theatre. The movement of the camera travels the dance across sites, dimensions, and textures.

The videographer returns to the lower level capturing the dancers again from the side of the stage, showing us a back view of their dancing to compliment the proscenium stage view that the audience traditionally enjoys. His presence is palpable — hidden behind the monstrosity of the camera is an elegant dancer whose corporeality leads the piece. He is sweating showing his physical labour that is akin to the dancers.

The electricity goes off. Silence. Still. My feet now touch the ground. Water.

The women slow or stop moving. He walks to the front and center of the stage, filming the audience, which is mostly still except for some hand waves and movements of audience members fanning themselves with printed programs.

Melodic music appears and the dancers switch to a pedestrian mode of removing the tape and sweeping the floor as Baltzis gradually exits the stage and returns to the backstage view, which is replaced with an image of the sky and clouds.

Waierstall’s multidisciplinary piece combines the visual and kinesthetic experience. The visual composition contains the architecture of the theatre, the arrangement of bodies in space and on screen punctuated with the use of the white tape. The kinesthetic element comes through the physical movements of the dancers and the videographer and the camera led movements on screen. The movement choices, structure, and scenery of the live bodies and screened choreography along with kinaesthetic perception of the dancers for the audience relates to Mark Franko’s idea that dance pairs “performer’s discourse of sensation with the spectator’s discourse of visual reception” (Franko 2011, p.1). Waierstall provides an experience for the audience that is visual, cinematic, kinesthetic, and emotional that is in line with Anna Pakes notion that dance is “inevitably perspectival” (2011, p. 34). For Waierstall, the perspectives are many and complex, challenging the audience with a complex aesthetic experience. As a dancer, I can imagine what the movement feels like, furthermore, I can imagine the cognitive process of rehearsing and performing the work, but I wonder what the experience is like for everyone else whose sense of embodiment may be vastly different. Waierstall’s work is an experience in visual and video art along with the experience of kinesthetic element of dancers moving on stage and screen. The audience has a sensory task to absorb the architecture of the stage, the hidden parts of the theatre including its industrial design and the auditorium, the composition of bodies on stage and on screen, the aural landscape of spoken word and two very different musical compositions, and the corporeal manifestations of the dancers in two mediums.

Waierstall exposes some of the skeletons of the creative process (text, camera work) yet draws attention to the corporeality of the dancers as the key element in creation, presentation, and reception of dance. The work displays the construction of the work with narration of instructions for movement, as well as, the presence of the camera on stage. Prior to the actions taken by the dancers, initially in rehearsal and then on stage, instructions and score are simply ideas that require the corporeal efforts to create dance. As Waierstall exposes the structure, the script, and mechanics of choreography, she allows dancers to communicate ideas with their physical subjectivity. Harmony Bench’s writing describes the process of performing choreography, the score, which is important to understanding the role of dancers in the performance of choreography as way to enliven dance as she states

“Gestures, steps, moves, movement phrases, dance routines, somatic practices, choreographic scores:

all of these exist as movement ideas that take shape through corporeal instantiation and interpretation.

They travel contagiously and accrue affective weight and meaning as they travel across the bodies

that come to perform them. Embodiment activates these objects” (2020, p. 162)

It is the dancers moving that brings life to the score with their embodied response to the spoken word, camera, and space. Without the presence of Marcouldes, Glymitsa, and Baltzis, the stage and screen would remain blank. They enliven the score as creative and originative collaborators.

The work explores relationship between live performance and the use of mediated image in dance by presenting dance in both of these conditions. The experience of watching screendance as opposed to a live performance may be critiqued according to Walter Benjamin’s idea that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” (quoted in Rosenberg 2012, p. 22). Furthermore, Harmony Bench states that “the move from stage to screen has been criticized for abandoning precisely what makes live performance appealing: risk, spontaneity, ephemerality” (Bench, 2006, p. 89), which Waierstall dispels with the immediacy of her work. Waierstall’s inclusion of live-action videodance in a proscenium theatre staged performance radically alters thinking around live and screened performances. The sense of responsiveness and immediacy is amplified with the spoken instructions which dancers seem to interpret in that moment creating an idea that choreography is materialised on stage in real time providing the excitement of a live performance and creation.

In Waierstall’s work, the inclusion of live performance along with screened dancing and instructional texts, deconstructs choreography allowing the audience multiple access points into the performance. The screendance methodologies draw attention to the details of the movement and choreographic possibilities afforded by the camera providing a deeper insight into the performance. By including the process of filming dance whilst projecting it, the choreographer exposes the process of making videodance, the movement of the videographer, the apparatus, and immediate directorial and editing decision making that amplifies movement and its possibilities. Screendance in Waierstall’s piece simultaneously offers a documentation of performed movement and a subsequent treatment through the editing process.

At the same time, the live production of screened dance creates a heightened experience of the choreography and dancers’ corporeality as it alters the number of dancers audience watches, their size, and perspective. The dancers are replicated, enlarged, multiplied by the camera, making the work feel much larger than a duet of dancers with a presence of a camera man. The microscopic technology of the camera allows for the audience to access details not available to the natural eye, such as the way the fabric textures react to the movements of the dancers. The camera is instrumental to dance on screen as it guides the gaze on to the body, providing a way of seeing that is particular to that instrument and vastly different to a viewing of a live performance. Dance on screen shifts live performance to mediatized representation and the dance “is reduced to the smallest sum of its parts” (Rosenberg 2012, p. 1). Each gesture is viewed in isolation allowing for a microscopical investigation therefore changing the nature of the way composition is conceived and viewed. The inclusion of video dance offers a potential to create intimacy with the viewer as it invites the spectator to consider the details of the choreography, which play a significant role in the way “the filmic apparatus constructs a representation of the dancing body that can appeal to a mass audience” (Dodds 2001, p. 37). The work relies on a complex relationship between the dancing body and the technology, which includes the choreography for the stage, the camera, and the cameraman, creating a collaborative, hybrid dance making.

The screen, and particularly the live feed in the work, adds another layer to the choreographic outcome. The camera work and its immediate projection alters the activity of the dancers. As Douglas Rosenberg, an esteemed scholar of screendance explains “method of apprehension (the screen) modifies the activity it inscribes (dance); in doing so it codifies a particular space of representation and, by extension, meaning” (2012, p. 3). The inclusion of the screened images of dance do not serve as a trick or gimmick, but rather invites the audience to consider other meanings of this dance. This choreography combines text, music, movement, filming, and screening assaulting the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewers and demanding a consideration of political meanings communicated. The work skilfully combines the live performance of the dancers and videodance interpretation of the same choreography. Waierstall bridges over the emotional attachment that may be created between the spectator and the corporeality of the performer in screendance by including both the live and recorded performance. Her work supports Douglas Rosenberg’s (2012) idea that screen dance actually recorporealises the live event by doubling the experience of the performers’ (including the videographer) corporeality. The dancers’, and videographer’s, corporeal presence makes the work visceral.

The choreography expands the idea of site-specificity of the theatre and screen within the traditional setting of a proscenium theatre. With the aid of the camera, various parts of the theatre usually hidden from the audience are used as places to perform and transport the performers. Furthermore, screendance places choreography in the site-specificity of media space making dance into a malleable, fluid, and digitally compatible corporeal text. In Waierstall’s piece the audience clearly sees the dancers in their physical location, yet by transporting dance onto a screen, performers become dissociated from a particular location, which allows access to a heightened, media-enabled mobility through camera work. Bench writes in relation to screendance that dancers “abstracted from built or natural environments that would situate their movement, bodies wander through space with an illusory freedom, unrestricted by physical or ideological barriers” (2008, p. 37). Deeply grounded in their physical presence on stage or in the auditorium, the experience of watching dancers transported into new locations on screen provides an immense sense of wander and freedom to the audience. They occupy an imaginary space that is in vast contrast to the loss of freedom experienced during Covid-19 pandemic.

The choreography exists in the intersection between the movement of the dancers, the choreography of the videographer and the camera, and the projected images on screen. The work creates a quiet tension, captures the attention of the audience, and sustains the steady, sustained manner throughout the work. At a time where the world is facing unprecedented difficulties of dealing with a harrowing virus, a crumbling economy, and a mental health crisis connected to fear and social distancing, Waierstall work provide an escape and a potent commentary. She has the ability as a dance maker to communicate with sustained tension that rejects the dramatic and extremely emotional outbursts. Although the work exposes the mechanisms of performance construction, it is poetic with words and movements. It simultaneously forces the audience to face the practicalities of the Covid-19 mandated order of things with mask wearing, social distances, and over-reliance on digital communication, however the work is deeply rooted in artistic sensibilities and pushes the dance form forward.

Bibliography

Bench, H. (2008) “Media and the No-place of Dance,” Forum Modernes Theater, 23.1, pp. 37-47.

_______. (2020) Perpetual Motion: Dance, Digital Cultures, and the Common. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

Dodds, S. (2001) Dance on screen: genres and media from Hollywood to experimental art. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pakes, A. (2011) ‘Phenomenology and dance: Husserlian meditations’, Dance Research Journal, 43(2), pp. 33-49.

Rosenberg, D. (2012) Screendance: inscribing the ephemeral image. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comments are closed.